Understanding Jazz Guitar Chords

When it comes to understanding jazz guitar chords it helps to realise that there are only really four different ‘families’ of chord-types. In this understanding jazz guitar chord lesson we will start from first principles and learn the foundations of the jazz guitar sound.

If you struggle with any of the following you may find the following information a little challenging. If this is the case, I strongly recommend that you check out The First 100 Chords for Guitar before launching into this book.

Understanding Jazz Guitar Chords: Forming chords

A chord is defined as any group of three or more notes played together. They are normally formed by stacking notes on top of each other from a particular scale. Most of the chords in this lesson are formed from harmonising the major scale.

To form a chord, we simply stack alternate notes from a scale. For example, in the scale of C Major:

C D E F G A B C

We take the first, third and fifth notes (C E and G), and play them together to form a C Major chord.

(C) D (E) F (G) A B C

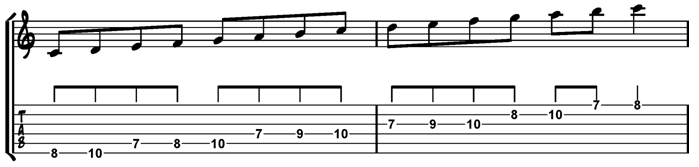

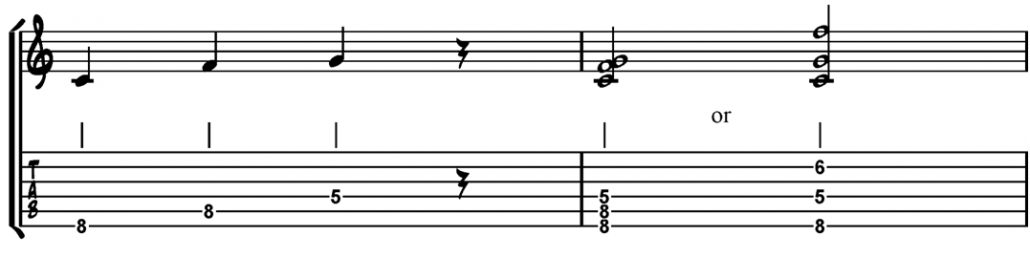

Understanding Jazz guitar Chords Example 1a:

If you notice, we took the first note C, then skipped the next note (D) and landed on the third note E. We repeated this process and skipped the fourth note (F) and landed on the fifth note G. The notes played together in this way are called a triad.

The first, third and fifth notes of a major scale form a major chord. This is true of any major scale. This chord is given the formula 1 3 5.

The formula 1 3 5 in C Major gives us the notes C E and G, however, we can alter any of the notes to form a different type of chord. For example, if we flatten the third we generate the formula 1 b3 5. We now have the notes C Eb G.

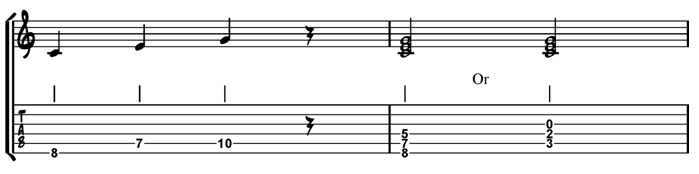

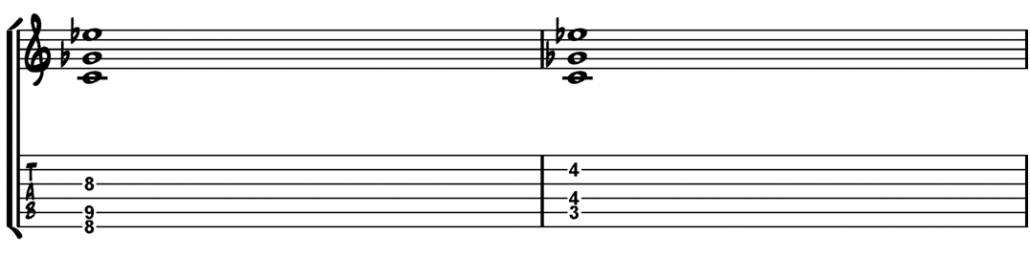

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1b:

As you can hear, this structure has a very different sound from the previous major chord.

Any chord with the structure 1 b3 5 is a minor chord. In fact, any chord that contains a b3 is defined as a minor sound.

We can also flatten the 5th of the chord. The structure 1 3 b5 is not very common in music although it does sometimes occur in jazz. However, the structure 1 b3 b5 occurs frequently. It is called a diminished or occasionally a minor b5 chord.

The formula 1 b3 b5 built on a root of C generates the notes C Eb Gb.

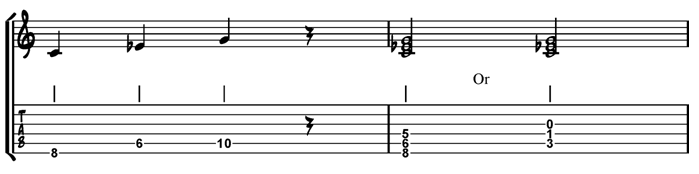

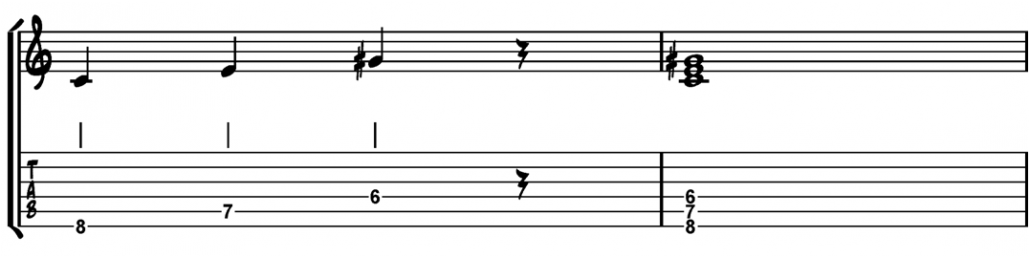

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1c:

The above shape is a bit of a stretch to play on the guitar, but the notes do not have to be played in this order. They can be played more comfortably like this:

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1d:

To achieve this voicing, I moved the b3 of the chord up by one octave.

As you can hear, the diminished chord has a dark and sinister air to it.

The three triads you have learned so far are

1 3 5 Major

1 b3 5 Minor

1 b3 b5 Diminished or just ‘Dim’

Most chords you come across in music, no matter how complicated can normally be categorised into one of these basic types. Jazz chord progressions are normally formed from richer sounding ‘7th’ chords, which are the focus of my book, The First 100 Jazz Chords for Guitar.

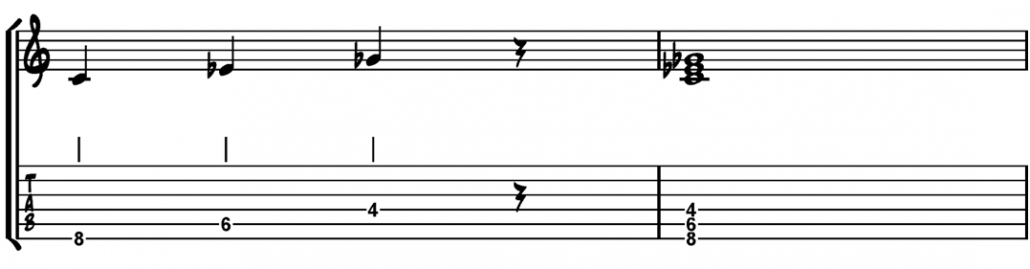

There is, however, one more permutation that crops up occasionally, it is the augmented triad, 1 3 #5.

From a root note of C, the notes generated by this formula are C E G#. There are two tones between each of the notes of the chord.

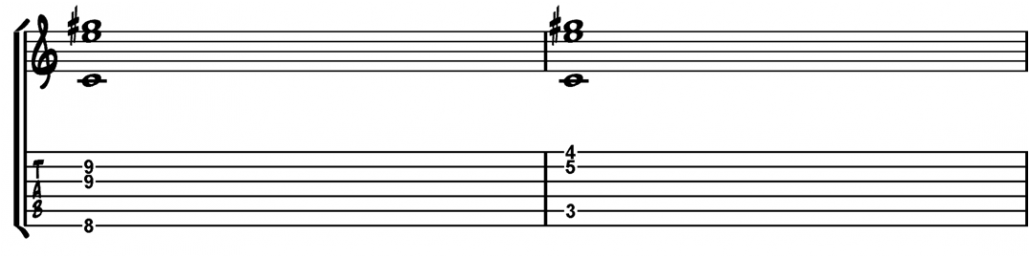

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1e:

Two useful voicings of the augmented (Aug) triad are

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1f:

Finally, there are two types of triad that do not include a 3rd. These chords are normally named ‘suspended’ (or just ‘sus’ chords), as the lack of the 3rd gives an unresolved feel to their character.

In a ‘sus’ 2 chord the 3rd is replaced with the 2nd of the scale, and in a sus4 chord, the 3rd is replaced with the 4th of the scale.

In C, the notes generated by the formula 1 2 5 are C D and G.

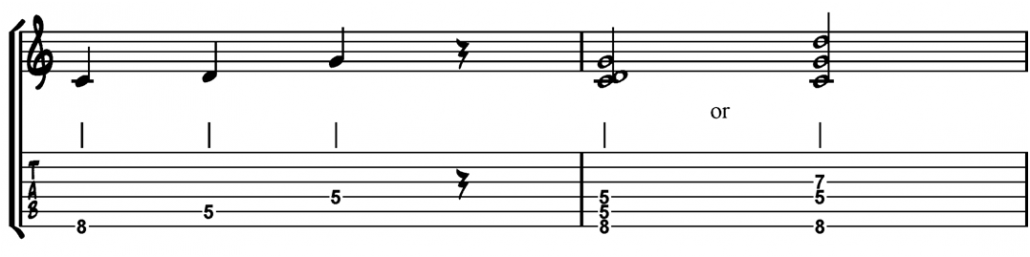

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1g

The notes generated by the formula 1 4 5 are C F and G.

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1h

It is first important that you learn to play some useful chord voicings of these basic triads as they do sometimes occur in jazz chord charts, especially in early ‘swing’ jazz.

In any chord, it is acceptable to double any note. For example, a major chord could contain two roots, two 5ths and only one 3rd. There were rules to govern their use in ‘classical’ times, although these days there are common chord shapes or ‘grips’ on the guitar that are frequently used. This is a big realisation when Understanding Jazz Guitar Chords.

As the focus of this book is on 7th chords, which are more common in jazz, only a few of the basic triad chord shapes are shown here.

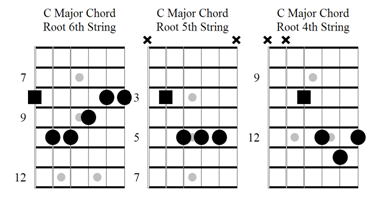

Major Chord Shapes:

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1i:

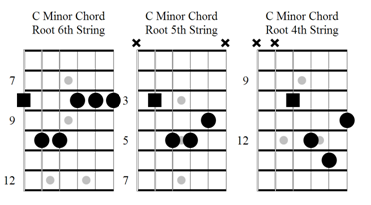

Minor Chord Shapes:

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1j:

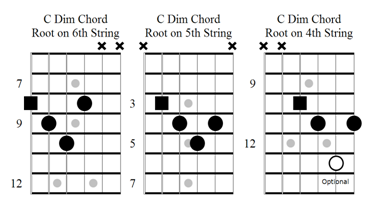

Diminished (minor b5) Chord Shapes:

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1k:

You probably already know most of these shapes, but if you don’t, my advice is to ignore them for now while we get focused on 7th chords. You can come back to these voicings as a reference when you need them.

To create a major 7th chord we simply extend the ‘1 3 5’ formula by an extra note so it becomes ‘1 3 5 7’.

Instead of C E G we now have C E G B:

(C) D (E) F (G) A (B)

Don’t worry about learning the following few chord shapes. The following shapes are just for illustration, some of them aren’t great voicings and are shown just for reference.

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1l:

In these voicings, I have changed the order of the notes to make the chord playable on the guitar. The chord is now voiced 1 5 7 3.

As the major 7th’s chord formula is 1 3 5 7, you might expect that the minor 7th’s formula would be 1 b3 5 7. This, however, is not the case.

To create a minor 7 chord we add a b7 to a minor triad. The formula is 1 b3 5 b7.

The formula 1 b3 5 b7 built on a root note of C generates the notes C Eb G Bb.

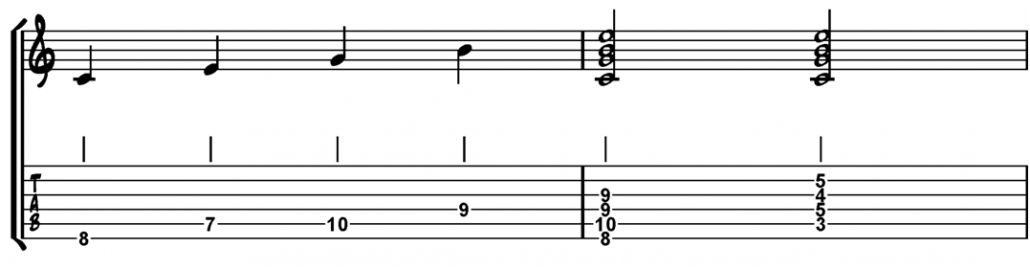

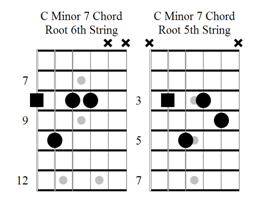

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1m:

Once again, the notes in the lower chord voicing have been rearranged to make the voicing playable on the guitar.

As you’re probably wondering, a minor triad with a natural 7 on the top 1 b3 5 7 is called a “minor major 7th” or m(Maj7) chord. They are given this name because they are minor triads with a major 7th added on top.

When we extend a minor b5 chord to become a 7th chord, we once again add a b7, not a natural 7. In fact, it is a general rule that if a triad has a b3, it is more common to add a b7 to form a four-note ‘7th’ chord.

As you can see in the previous paragraph, this is not always the case, so be careful when applying that ‘rule’.

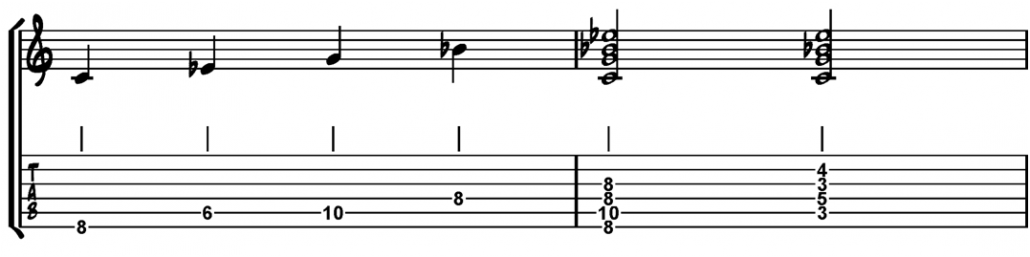

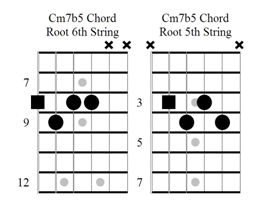

A (diminished) minor b5 chord with an added b7 has the formula 1 b3 b5 b7 and generates the notes C Eb Gb Bb when built from the root note of C. This chord is named ‘Minor 7 flat 5’ or m7b5 for short. It also is common for m7b5 chords to be referred to as ‘half diminished’ chords.

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1n:

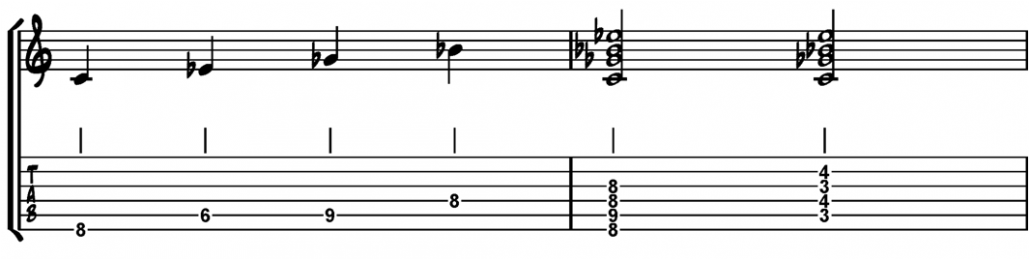

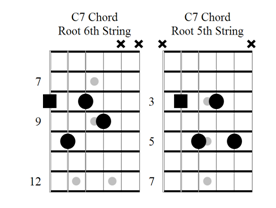

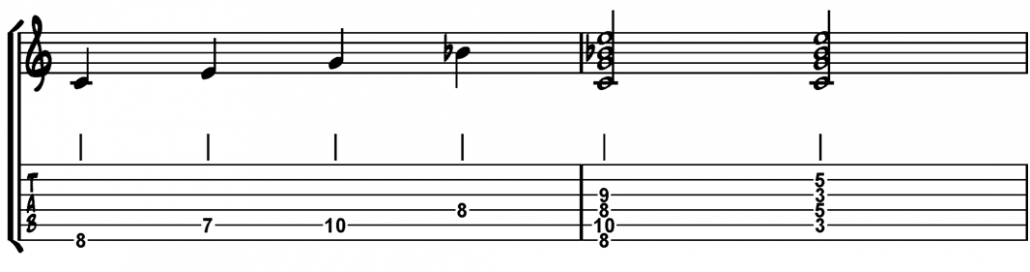

Finally, we come to one of the most common chords in jazz; the dominant 7 chord. It is formed by adding a b7 to a major triad. 1 3 5 b7. With a root of C this formula generates the notes C E G Bb.

Because of the fundamental major triad 1 3 5, this chord is a ‘major’ type chord, but the added b7 gives it an extra bit of tension.

Jazz guitar Chords Example 1o:

These four chord types can be summarised:

| Chord Type | Formula | Short Name |

| Major 7 | 1 3 5 7 | ‘maj7’ |

| Dominant 7 | 1 3 5 b7 | ‘7’ |

| Minor 7 | 1 b3 5 b7 | ‘m7’ |

| Minor 7 b5 | 1 b3 b5 b7 | ‘m7b5’ |

It is the modern way of thinking that all chord types in jazz function in one of the above contexts. What this means in simple terms is that even a complex chord, such as C7#5b9, can be viewed in its simplest form as just C7.

A C Minor 11 chord can be simplified to become a Cm7-type chord and a C major 9th chord can be reduced to a Cmaj7-type chord. This is very useful when viewing jazz tunes from a soloing perspective. There are a few exceptions to these rules, and these will be addressed individually.

This idea of chord ‘types’ or families is especially useful when we’re just starting out, or when we’re given a particularly difficult chord chart to read with little preparation time.

Understanding Jazz Guitar Chords: Chord Families

Maj7-type chords

This is a gross simplification, but any chord name that contains a “Maj”, “Major” or “6” can normally be seen as a type of a Major 7 chord. If you see BbMaj9 or Bb Maj6, more often than not it is OK to play a BbMaj7.

Now, if you’re an experienced jazzer, you may be yelling at me, because sometimes it’s not OK to substitute a Major 7 for a “6” chord. However, while you’re starting out, it’s a useful “ballpark” approach that will allow you to play through a tune. Do you really want to run into a brickwall when you know every chord in a tune apart from Bb6, or do you want to get through it with a very slight potential clash when you play a BbMaj7 instead?

Let’s get you playing and we can worry about the tiny details later. I wasted many years worrying about this kind of thing, and as a result I didn’t make the progress I could have. When you learn English as a child, you don’t worry about every possible irregular verb, you just get corrected by adults and remember the exceptions.

How often do you hear a child say something like, “I ride-ed my bike”? We all know that the past tense of ride is rode, but if the child in question had to worry about every possible irregular verb when they were trying to communicate they’d never open their mouth. I promise you it’s better to learn by doing. Understanding jazz guitar chords is a lot like learning to intuitively understand language.

Minor7 (m7)-type chords

The m7 chords are a bit more forgiving. Anytime you see a “min” (or “m”) you can normally play a m7 chord. Again, there are a couple of specific exceptions, but anytime you see a Bbm, Bbm9, Bbm11 etc., you can simply play a Bbm7 chord.

The only time you can’t do this is when you see a Bbm(Maj)7. That’s a really specific voicing and should be played as written.

Dominant 7-type chords

Any Dominant 7, 9, 11, or 13 chord can be played as a dominant 7 chord. The only real exceptions are when you see a “7sus” chord, as the composer doesn’t want you to play the 3rd. Again, don’t worry about this for now, that is a rare occurrence. However, as you will learn later when understanding jazz guitar chords, jazz musicians play a lot of chords called “altered” dominant chords. These look terrifying on paper and have names like Bb7b9, Bb7#5 or even Bb7b5#9.

For now, ignore the algebra at the end and play them all as Bb7 chords.

Minor 7b5 (m7b5)-type chords

You won’t see too many variations of m7b5 chords, but sometimes chords like Bbm9b5 or Bbm7b5b9 do occasionally crop up. Again, play both of these as a m7b5.

So there we have it, at the end of this first long lesson, you understand how to build almost every important guitar chord, and more importantly, simplify your thinking into just four important chord types.

If you see the chord progression:

Cm11 – F7#5#9 – BbMaj9 – Gm9

You now know you can simply play

Cm7 – F7 – BbMaj7 – Gm7.

OK, it isn’t exactly what’s written but it is close enough for government. You’ll sound great, you’ll get through the gig, and 99.9% of people won’t even notice.

OK, now you’re ready for lesson two! Click Here to learn more about jazz guitar chord voicings

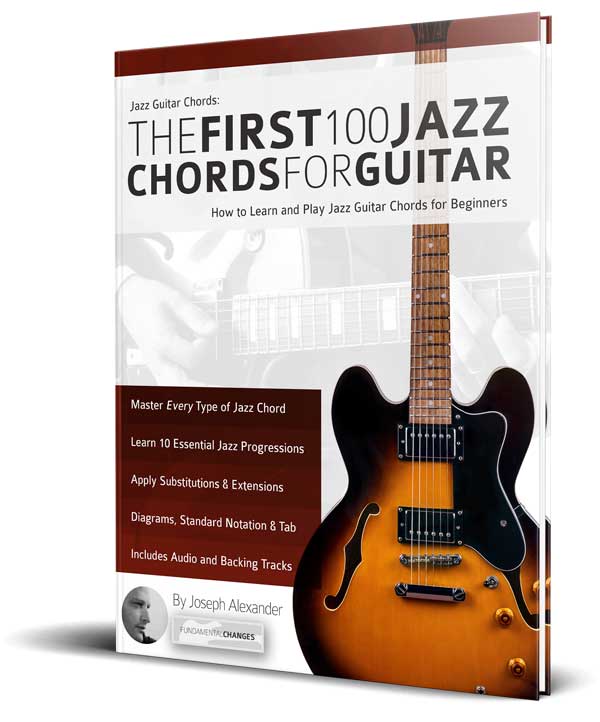

Or learn much more by checking out my new book The First 100 Chords for Jazz Guitar!

“The artists you work with, and the quality of your work speaks for itself.”

Tommy Emmanuel

© Copyright Fundamental Changes Ltd 2025

No.6 The Pound, Ampney Crucis, England, GL7 5SA