How to Use 4 Note Groupings, (Coltrane Tetrachords), to Spice up your Solo

Using 4 Note Groupings (tetrachords) in Improvisation

By Pete Sklaroff

Whilst many guitar players continue to concentrate on diatonic scales and arpeggios as their primary approach to improvisation, other players have been exploring alternative musical directions with a view to finding fresh melodic material. One such approach involves the playing of specific and predetermined melodic patterns (in this case 4 note motifs or ‘tetrachords’) to augment an existing improvisational approach. This lesson is going to examine this concept in detail and show you how you can integrate this into your own playing.

Background

I first came across this approach through the work of the famous jazz saxophonist John Coltrane on his landmark recording ‘Giant Steps’ from 1959. On the title track, Coltrane utilises a number of four note melodic patterns, or tetrachords, to negotiate the composition’s challenging and fast moving harmony. By playing these melodic groupings, Coltrane makes the piece sound incredibly fluid and exciting, whilst remaining harmonically accurate to the rapidly shifting key changes within the composition.

Although the use of these patterns is very closely associated with Coltrane (and players influenced by him) you can easily incorporate them into your own playing regardless of whether you are wanting to play in a jazz style or not, as they provide a clear and accurate melodic device that when used appropriately, will outline chord changes very clearly.

The patterns are all constructed within a maximum interval of a perfect fifth and do vary slightly according to their harmonic application, as we will see in the tables below. Some chord types also share the same pattern (see major & unaltered dominant patterns for example) because there are no intervals above a perfect fifth contained within these patterns and therefore no 6th or 7th degree is present.

Construction & Application of Tetrachords

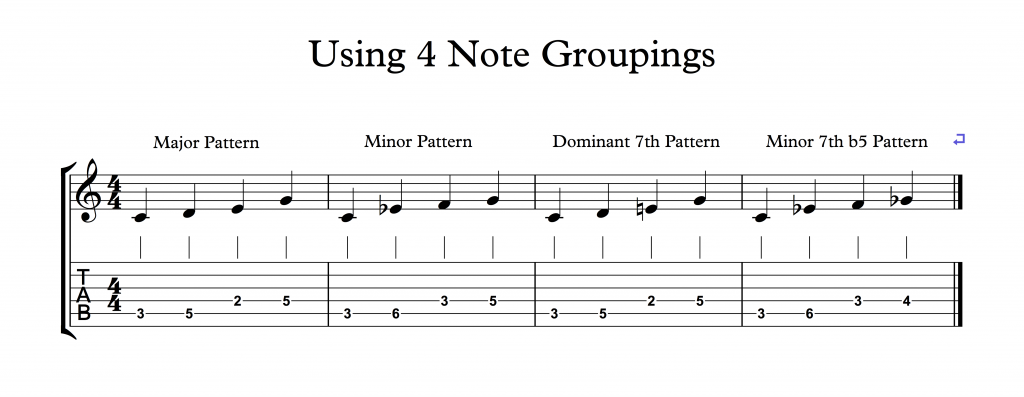

The table below illustrates five (what I refer to as ‘primary’) groupings that cover Major, Minor, Dominant 7th & Minor 7b5 chords plus a Dominant 7th b9 chord (n.b. the regular dominant 7th pattern does not include any chromatic alterations and is best employed on un-altered dominant chords)

Let’s now examine how these patterns are created and where they can be applied. In terms of their intervallic formula, the five primary patterns are constructed like this:

|

Table of 4 Note Cell Patterns |

|

| Major Chords | R, 2, 3, 5 |

| Minor Chords | R, b3, 4, 5 |

| Dominant 7th (unaltered) | R, 2, 3, 5 |

| Minor 7b5 | R, b3, 4, b5 |

| Dominant 7th (b9) | R, b2, 3, 5 |

The next example (shown below) now illustrates four of these patterns in both standard musical notation and tablature. There are of course numerous ways of fingering these melodic groupings on the fingerboard, however I have chosen to just write out one example for this lesson and I would highly recommend working on others in your practice sessions.

I’ve also written the patterns employing only quarter notes (crotchets) as this is probably the best way to work with them initially (you could also use eighth notes/quavers if you’d prefer) By using simple rhythms, you can focus more on hearing how these patterns operate against the underlying harmony.

Once you have learnt the formula patterns above, you can immediately begin to use them in your everyday practice over progressions that employ these chord types. To do this you need to simply find which pattern fits which chord and then apply it.

I would highly recommend playing the patterns both ascending and descending at first and until you are thoroughly familiar with them. Once you have achieved some fluency with this approach, you can then experiment with starting on different pitches other than the root or fifth and mix up the four notes in a variety of different permutations.

It is also important at this stage to keep to the same rhythm throughout as you work through the patterns, ensuring complete accuracy in their application. When you become more familiar with the patterns you can vary the rhythms you employ, but this should be only when you are 100% sure of them.

Further Thoughts

These patterns bridge the gap somewhat between traditional diatonic scales and arpeggios, but should not be viewed as a replacement for either in your regular playing. They are offered as an alternative approach that you can employ to add a different melodic flavour to your playing and can (especially if used sparingly) really enhance a solo.

I hope you enjoy working with these patterns,

Happy Practicing,

Pete

Pete Sklaroff

Pete Sklaroff is the former Assistant Head of Music and Head of Jazz Studies at Leeds College of Music in West Yorkshire (where he taught for over 20 years) and he now works freelance as a professional guitarist, session musician, clinician and music educator/guitar tutor in the UK. His career spans over 25+ years as a professional musician and he has toured and recorded extensively in that time.

“The artists you work with, and the quality of your work speaks for itself.”

Tommy Emmanuel

© Copyright Fundamental Changes Ltd 2025

No.6 The Pound, Ampney Crucis, England, GL7 5SA