Chord Extensions to Dominant 7 Chords

This lesson looks at the idea of chord extensions on guitar.

In the first lesson in this series you learnt how to build the essential chords we use every day. In music, it is common to add diatonic ‘extensions’ and chromatic ‘alterations’ to dominant 7 chords. A natural or ‘diatonic’ extension is a note that is added to the basic 1 3 5 b7 chord, but lies within the original parent scale of the dominant chord. In other words, to form an extended dominant chord we continue skipping notes in the scale, just as we did when we originally learnt to form a chord.

We can extend the basic 1 3 5 b7 chord formula to include the 9th, 11th and 13th scale tones.

These extensions occur when we extend a scale beyond the first octave. For example, here is the parent scale of a C7 chord (C Mixolydian):

| C | D | E | F | G | A | Bb | C | D | E | F | G | A | Bb | C |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | b7 | 1/8 | 9 | 3 | 11 | 5 | 13 | b7 | 1 |

Notice that in the second octave, if a note is included in the original chord it is still referred to as 1, 3, 5, or b7. This is because the function of these notes never changes in the chord: A 3rd will always define whether a chord is major or minor and the b7 will always be an essential part of a m7 or 7 chord.

The notes between the chord tones are the notes that have changed their names. Instead of 2, 4 and 6, they are now 9, 11, and 13. These are called compound intervals

In very simple terms you could say that a C13 chord could contain all the intervals up until the 13th:

1 3 5 b7 9 11 and 13 – C E G Bb D F and A

In practice though, this is a huge amount of notes (we only have six strings), and playing that many notes at the same time produces an extremely heavy, undesirable sound because many of the notes will clash with one another.

The answer to this problem is to remove some of the notes from the chord, but how do we know which ones?

There are no set rules about which notes to leave out in an extended chord, however there are some guidelines about how to define a chord sound and what does need to be included.

To define a chord as major or minor, you must include some kind of 3rd.

To define a chord as dominant 7, major 7 or minor 7, you must include some kind of 7th.

These notes, the 3rds and 7ths are called guide tones, and they are the most essential notes in any chord. It may surprise you, but these notes are more important than even the root of the chord and quite often in jazz rhythm guitar playing, the root of the chord is dropped entirely.

We will look more closely at guide tone or ‘shell’ chord voicings in another lesson, but for now we will examine common ways to play the extensions that regularly occur on dominant chords in jazz progressions.

To name a dominant chord, we always look to the highest extension that is included, so if the notes were 1, 3, b7 and 13 we would call this a dominant 13, or just ‘13’ chord. Notice that it doesn’t include the 5th, the 9th or the 11th but it is still called a ‘13’ chord.

As long as we have the 3rd and b7th a chord will always be a dominant voicing.

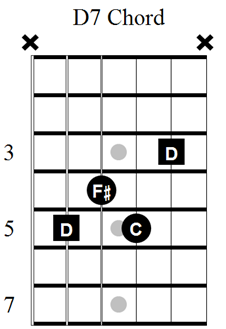

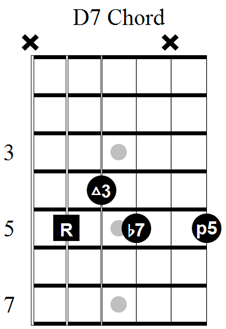

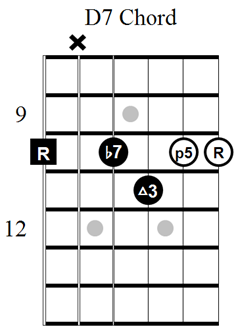

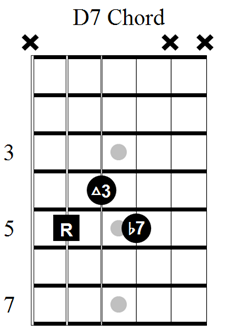

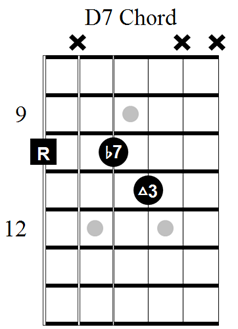

We will begin by looking at a fairly common voicing of a D7 chord. In the following example, each interval of the chord is labelled in the diagram.

In D7 the intervals 1 3 5 b7 are the notes D, F#, A and C.

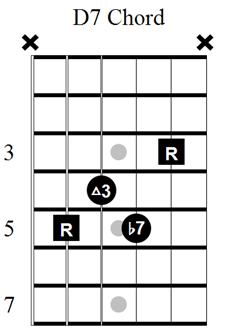

Dominant 7 Chord Extensions Example 3a:

The ‘triangle 3’ symbol is shorthand for ‘major 3rd’.

As you can see, this voicing of D7 doesn’t include the 5th of the chord (A).

Here is the extended scale of D Mixolydian (the parent scale of D7).

| D | E | F# | G | A | B | C | D | E | F# | G | A | B | C | D |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | b7 | 1/8 | 9 | 3 | 11 | 5 | 13 | b7 | 1 |

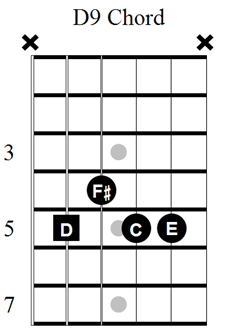

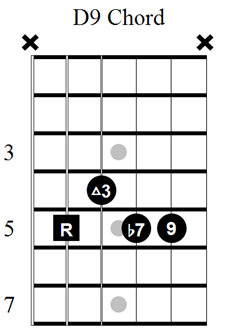

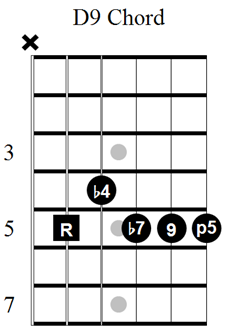

We can use this voicing of D7 to form a dominant 9 or ‘9’ chord. All we need to do is add the 9th of the scale (E) to the chord. The easiest way to do this is to move the higher-octave root (D) up by one tone and replace it with an E.

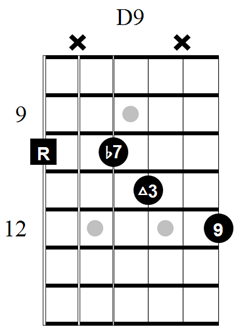

Dominant 7 Chord Extensions Example 3b:

Look carefully to make sure you understand how I replaced the root of the chord with the 9th of the chord to form a dominant 9 or ‘9’ chord.

The intervals contained in this chord voicing are now 1, 3, b7 and 9. We have the 1, 3 and b7 defining the chord as dominant and the 9th (E) creating the extended dominant 9th chord.

Dominant 11th or ‘11’ chords are less common and need some special care because the major 3rd of the chord (F#) can easily clash with the 11th (G).

We will gloss over 11th chords for now and come back to them later, although the most common way to form an 11 chord it to lower the 5th of a dominant chord by a tone. The lowering of the 5th is generally voiced one octave above the 3rd otherwise a semitone clash between the 3rd and 11th can occur.

Here is another voicing of a D7 chord, this time it does contain the 5th:

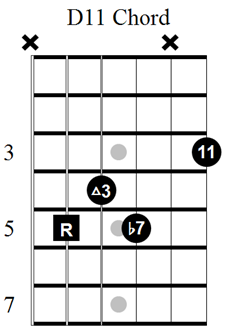

Dominant 7 Chord Extensions Example 3c:

By lowering the 5th (A) by a tone to the 11th (G) we form a dominant 11 or ‘11’ chord.

Dominant 7 Chord Extensions Example 3d:

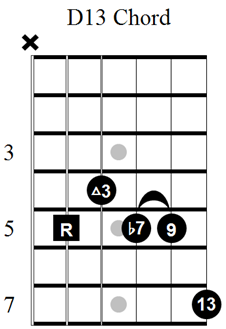

Dominant 13 chords are much more common in jazz than dominant 11 chords. They are normally created by raising the 5th of a dominant 7 chord by one tone so that it becomes the 13th (6th). It is common to include the 9th of the scale in a 13th chord, but it is by no means necessary.

By combining the last two ideas we can form a D9 chord with the fifth on the 1st string of the guitar:

Dominant 7 Chord Extensions Example 3e:

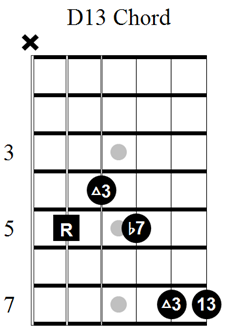

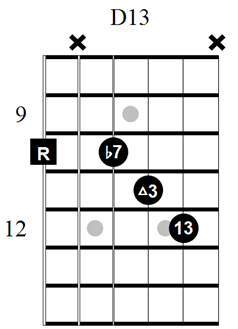

By raising the 5th by a tone we can reach the 13th degree (interval) of the scale. The chord is given first with the intervals shown, and then with the recommended fingering:

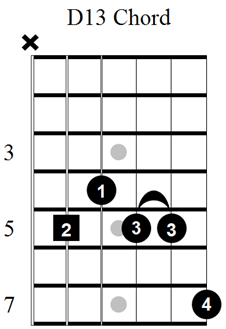

Dominant 7 Chord Extensions Example 3f:

As I’m sure you’re starting to see, adding extensions to dominant chords is simply a case of knowing where the desired extension is located on the fretboard and then moving a nonessential chord tone to that location.

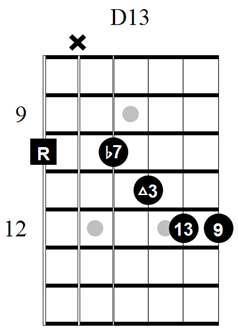

The above 13 chord can also be voiced slightly differently to achieve a subtly different flavour. We could replace the 9th with the 3rd:

Dominant 7 Chord Extensions Example 3g:

In this voicing there are two 3rd which is completely acceptable. You will probably find the preceding version with the 9th included to be a slightly richer sound.

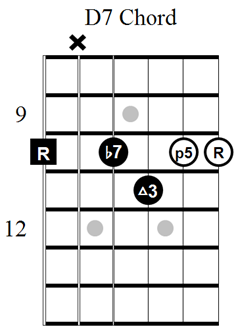

This approach can also be applied to a dominant 7 chord voiced from the 6th string of the guitar. Here are the root, 3 and b7 of a D7 chord with a 6th string root:

Dominant 7 Chord Extensions Example 3h:

The 5th and higher octave root of this chord are located here:

If you remember, we can raise the 5th by a tone to play the 13th of the chord, and we can raise the root of the chord by a tone to target the 9th.

The third diagram shows a 13 chord which includes the 9th. It is still a 13th chord whether or not the 9th is present.

The following two ‘shell’ voicings are extremely useful fingerings to know, as it is easy to add extensions to them while keeping the root of the chord in the bass. However, as you will learn in chapter fourteen, diatonic extensions are often added by the clever use of chord substitutions that replace the original chord.

You can learn much more about chord extensions in my best selling book: Guitar Chords in Context. Available on Amazon.

“The artists you work with, and the quality of your work speaks for itself.”

Tommy Emmanuel

© Copyright Fundamental Changes Ltd 2025

No.6 The Pound, Ampney Crucis, England, GL7 5SA